Introduction

Menstruation, a natural process but also a total inconvenience. In an attempt to manage the (mostly) monthly occurrence on top of the hassles of daily life, many people (women, transgender men, gender-queer) use hygiene and collection products that simply get the job done. As long as there is no leakage or pain associated, people will use and trust it, especially since frequency and dependability are in the same equation of menstruation and its maintenance. However, many disregard the potential health risks of either the products themselves or the materials used to make them. There also exists environmental aspects of menstruation that are not as evident to many. This post is determined to explore the holistic effects of varying feminine hygiene products associated with menstruation in hopes and getting one step closer to obtaining an answer to the arguably subjective question: What is the best product for menstrual hygiene management?

Vaginal Vulnerability

It is essential to first note the importance of mindfulness when it comes to deciding what we put near or into our vaginas. The vaginal ecosystem is rather sensitive compared to other regions of the the body. In order to stay healthy, the glands inside the vagina and the cervix release discharge that contains bacteria and dead cells. This is the way the vagina cleans itself and fights to prevent any type of infection. This introduces the importance of vaginal pH, the measure of how acidic one’s vaginal discharge is. A normal, healthy vagina usually has a pH of 4 but if it rises above 4.5, protection is decreased and the vagina becomes vulnerable to the growth of microorganisms that may cause disease or infection (Camerato, 2017). There exists a type of bacteria called lactobacilli that works to regulate the pH of the vagina but this regulation is easily disturbed leading to an increased possibility of vaginal infection. There is an even greater risk if certain feminine hygiene products we use contain ingredients or materials known to hurt rather than help the vagina and its maintenance. Because the vagina is made up of absorbent tissue, called epithelial tissue, it has a tendency to “soak up” chemicals from said products and increase the risk of things like infection and irritation. Therefore, being conscious of how external factors may affect the vagina’s ecosystem can protect one from numerous vaginal infections, especially during menstruation where one’s only concern is getting through the day without getting stained.

Types of Menstrual Products and Practices

Primary education on female puberty typically consists only of the introduction to sanitary pads and tampons. Sanitary pads are disposable, absorbent napkins that are worn on the underwear and collect menstrual blood. Tampons are plugs of absorbent material that are inserted into the vagina, expanding as it soaks up the blood. Not commonly discussed is the menstrual cup, a device made out of flexible silicone that is also inserted into the vagina to collect, rather than absorb, menstrual blood. Other products used during one’s menstrual cycle are vaginal douches, sprays, and powders. Although these products are not used to control blood flow, they act as supplementary tools for the upkeep of vaginal hygiene, specifically for its smell. While the list of feminine hygiene products is longer, those mentioned above will be further discussed in this post.

Sanitary Pads

One of the more widespread products are sanitary pads and panty liners. From being secured with pins to having a fastening adhesive, the commercialization of sanitary pads has undergone many changes, resulting in the use of new production techniques and materials. The FDA continues to claim that sanitary pads are safe but not many studies have been done to determine their health risks over a person’s lifetime. The most recent innovation has been the development of thinner pads with an absorbent core that does not contain cellulose. Nevertheless, the layered structure of the pad has three degrees of potential exposure when used: direct skin contact through the top sheet, indirect skin contact through the absorbent core and the perfume derivatives incorporated during production, and minor skin contact with the adhesive of the sanitary pad (Woeller, 2015). This exposure is continuous during one’s period as one single pad is worn for 4-6 hours during the day and for 8-12 hours overnight. These long intervals of use combined with the movement of everyday life make allergic reactions, irritation, and dermatitis common health effects of sanitary pads.

Tampons

Another common product used are tampons, which are made from synthetic ingredients that today mostly consists of viscose rayon due to the the increased incidence of Toxic Shock Syndrome, a condition caused by the release of toxins due to the overgrowth of a bacterium commonly found in the vagina known as staphylococcus aureus (Nicole, 2014). Most of the bacteria in the vagina is anaerobic meaning that they grow without the presence of oxygen. When the synthetic material of tampons is present, the bacteria responds to the change of environment by releasing toxins. The production of tampons has also been proven to produce dangerous by-products as cotton and wood pulp are bleached in order to deeply whiten the product. These by-products are called dioxins and have the potential to accumulate in the body due to simple one minute exposure. The dangerous potential of these chemicals have instigated the increased production of all-cotton tampons. While these have an impressively smaller correlation with Toxic Shock Syndrome, all tampons have the ability of creating small tears in the vagina that serve as openings for toxins and chemicals that are found in other menstrual products and everyday hygiene products like body washes and bath bombs (Camerato, 2017).

Menstrual Cups

Not commonly acknowledged are menstrual cups which are inserted into the vagina in order to collect blood. There are two types of menstrual cups, a vaginal cup and a cervical cup that is placed high into vagina. These products are made from silicone, rubber, latex or elastomer, allowing the menstrual cup to be reusable, only requiring it to be emptied every 4-12 hours and having it carefully cleaned and stored (Eijk et al, 2019). The process to insert and remove menstrual cups has the ability to cause pain, discomfort and irritation if done incorrectly. Their size, compared to tampons, and the unfamiliarity of its method of blood collection can be intimidating to some, preventing the increase in usage. However, the way that they are designed and made have caused fewer occurrences of bacterial infections and inflammation. There is also less leakage and potential of staining due to its positioning in the vagina. Overall, when used correctly, menstrual cups are deemed very convenient on top of other benefits that will be discussed later.

Vaginal Douches, Sprays and Powders

When the term menstrual product is mentioned, products that simply allow us to control the blood come to mind. However, there are products that are used to complement pads, tampons, menstrual cups, etc. These include vaginal douches, sprays and powders. Vaginal douching is the method of flushing out the vagina with water or other fluid mixtures. It is commonly used to wash away menstrual blood, to get rid of odors, and after sexual intercourse as a way to prevent contracting an STD or pregnancy. While many believe that this practice has many potential advantages, research has found a correlation between douching and vaginal infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, cervical cancer, pregnancy complications, and the transmission of STIs (Nicole, 2014). Vaginal douching is also associated with higher exposure of 1,4-dichlorobenzene, a compound commonly used as a deodorant or disinfectant. While it serves a purpose in mothballs and restroom urinal cakes, it is not safe to have near the vaginal ecosystem. This is a volatile organic compound that has evidence of carcinogenicity, the ability produce tumors (Ding et al., 2019). This compound has also caused menstrual disturbances, inborn malformations, and spontaneous abortions. Those with higher frequency of douche use are more susceptible to whole blood concentrations of 1,4-dichlorobenzene and the health risks mentioned above. When it comes to vaginal sprays and powders, these products are mostly used to control the natural smell of the vagina that tends to worsen during menstruation. While it is nice to feel fresh down there, these fragrant products can cause an imbalance in the vaginal pH, again introducing the vulnerability to toxins. There do exist cultural issues and societal expectations about how women should smell and take care of their bodies but taking into consideration the health risks that these beliefs produce, it is advisable to prioritize the overall well-being of such an important sex organ that could potentially affect the rest of the body.

Environmental Considerations

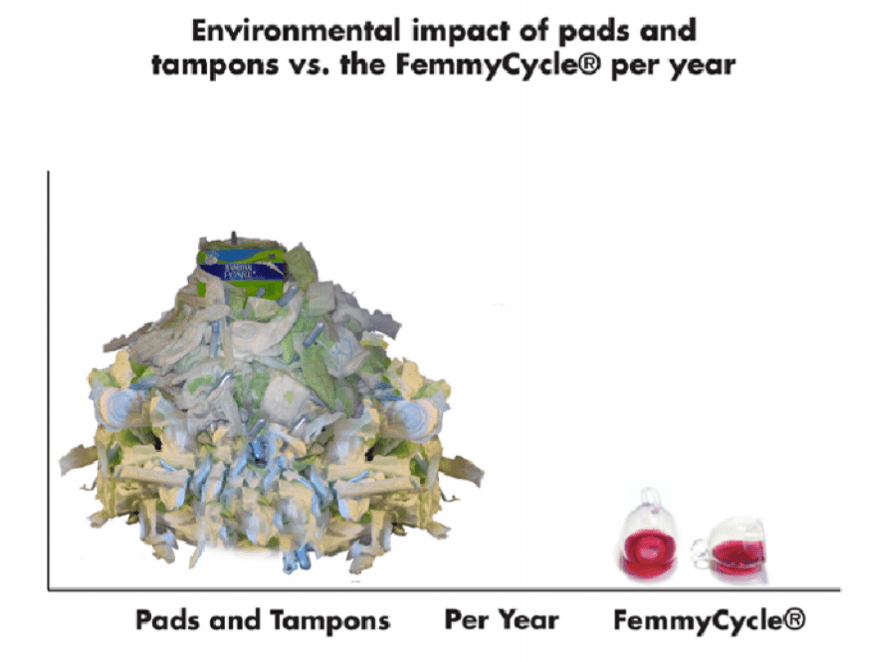

The previous discourse has provided information on the potential health risks and benefits on the environment of the vagina but one can sometimes get so caught up with everyday hassles that they are oblivious to the fact that our menstrual cycles also have an effect on the environment. “An average woman will use as many as 17,00 pads and tampons in her lifetime” (Shihata & Brody, 2014). The disposal of contaminated feminine hygiene products pollute the environment and will continue to do so as these products are a fact of life in many developed countries. In developing countries, many cannot afford to consistently buy sanitary pads or tampons, forcing them to resort to rags that also end up polluting the environment due to the lack of proper waste disposal. The production of menstrual products continue to advance, eliminating certain types of plastics and replacing them with cotton that is friendlier in terms of the vagina’s health. While this is still important for the well-being of the consumer, the pervasion of plastic in the environment continues to deepen as women try to manage a natural occurrence that, arguably, should not be considered a problem in the first place. Although the plastic applicators of tampons are recyclable, they are not accepted due to sanitary concerns. Many products also end up in the ocean when flushed down the toilet and sewer systems fail to deliver them to the appropriate location of disposal. The addition of individualized packaging for privacy has also increased the amount of waste produced by feminine hygiene products. While one can propose to get rid of packaging, applicators, or the wings on sanitary pads, society’s preference and expectation for these things would cause an uproar of discontent voices. Many may have no choice to seek an alternative to pads and tampons but those that would like a more efficient, environmentally friendly, and affordable product could consider using a menstrual cup. Although it may take some effort to get past personal reservations and unfamiliarity, menstrual cups are reusable, dependable and do not require constant spending. There is no disposal of contaminated products, lessening the burden of menstruation on the environment, an issue that should many did not ask for with the natural occurrence of menstruation.

Conclusion

The health of the vagina is very much influenced by behavioral habits as well as products used for its maintenance. While menstruation is something that we have learned to deal with in order to live our everyday lives, there is still a need for mindfulness and education on how we deal with this natural process. Simple effectiveness does not equate to feminine health. Products used in or near the vagina have the potential of harmful effects, whether that be acute inflammation or the deadly potential of Toxic Shock Syndrome. Becoming accustomed to certain practices and products in inevitable as one’s upbringing and education plays a large role in their socialization and habits. It is understandable to not question what has become so normalized, especially when certain resources and education are so limited, like that of feminine hygiene products. With a process that the average women spends 40 years dealing with, it is important to research and determine how female reproductive health can be exploited by presuppositions and expectations that have not fully considered their effects on longitudinal exposure and health. Preference is the main justification for the loyalty to certain products and practices but those are informed and considerate will be the ones to achieve greater health.

Sources

AM van Eijk, G Zulaika, M Lenchner, et al. Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability: a systematic review and meta-analysis Lancet Public Health (2019) published online July 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30111-2

Camerato, Ellie. “The Effects of Feminine Hygiene and Beauty Products on Vaginal Health.” Digital Commons @ Kent State University Libraries, Kent State University , 28 Apr. 2017, https://digitalcommons.kent.edu/starkstudentconference/2017/Presentations/35/.

Ding, Ning, et al. “Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds and Use of Feminine Hygiene Products Among Reproductive-Aged Women in the United States.” Journal of Womens Health, 2019, doi:10.1089/jwh.2019.7785.

Nicole, W. (2014). A question for women’s health. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.122-A70 Retrieved from https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/122-a70/.

Shihata, A., and S. Brody. “An Innovative, Reusable Menstrual Cup That Enhances the Quality of Women’s Lives During Menstruation”. Journal of Advances in Medicine and Medical Research, Vol. 4, no. 19, Apr. 2014, pp. 3581-90, doi:10.9734/BJMMR/2014/9640.

Woeller, Kara E., and Anne E. Hochwalt. “Safety Assessment of Sanitary Pads with a Polymeric Foam Absorbent Core.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, vol. 73, no. 1, 15 July 2015, pp. 419–424., doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.07.028.